Gigantic prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – that are technically superior to Victorian Engineering

“A scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it.” Max Planck

The word Dyke is commonly used to describe: A long wall or embankment built to prevent flooding from the sea or watercourse. The modern word ‘dike’ or ‘dyke’ most likely derives from the Dutch word ‘dijk’, with the construction of dikes in The Netherlands well attested as early as the 12th century. The 126 kilometres (78 mi) long Westfriese Omringdijk was completed by 1250 and was formed by connecting older dikes. The Roman chronicler Tacitus even mentions that the rebellious Batavi pierced dikes to flood their land and protect their retreat (AD 70). The word Dijk initially indicated both the trench and the bank.

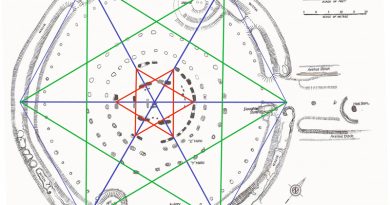

If you study archaeology at university or even on an ordinance survey map at length, you will notice strange earthworks on the sides of hills of Britain, with no rational explanation as to why they are where they are. At university, these features are mostly ignored, or an excuse is made for their construction. The reality is that these features do not make any sense unless there is another factor in operation that we have ignored or are oblivious to.

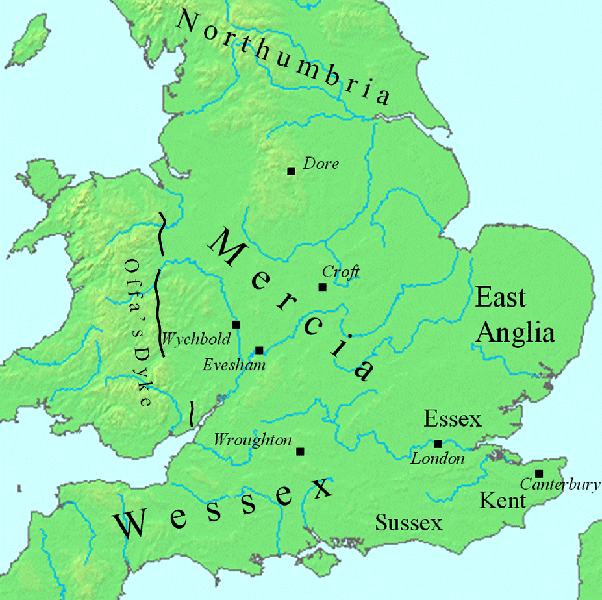

The first thing to notice is that the word ‘Dyke’ is associated with water. It does seem strange you would call an earthwork on top of a hill a Dyke, unless there was some history passed down through the years to its actual use. If we look at the most famous Dyke in Britain ‘Offa’s Dyke (that tracks the border between England and Wales), we notice that it is attributed to a Saxon King and therefore, could not be prehistoric. Or is this a clear indication of how archaeologists find excuses for these features rather than factual, empirical evidence?

“Offa’s Dyke (Welsh: Clawdd Offa) is a massive linear earthwork, roughly followed by some of the current border between England and Wales. In places, it is up to 65 feet (19.8 m) wide (including its flanking ditch) and 8 feet (2.4 m) high. In the 8th century, it formed some kind of delineation between the Anglia kingdom of Mercia and the Welsh kingdom of Powys.”

At face value, this seems to answer all the questions about dykes – except the water connection.

However, if you delve further down to look at the real evidence such as archaeological findings from Offa’s Dyke and any recorded written history. You will get a pretty different view on how constructed the Dyke. For example, the Roman historian Eutropius in his book, Historiae Romanae Breviarium, written around 369 (AD), mentions the Wall of Severus, a structure built by Septimius Severus, who was Roman Emperor between 193 and 211 (AD):

“He had his most-recent war in Britain, and to fortify the conquered provinces with all security; he built a wall for 133 miles from sea to sea. He died at York, a reasonably old man, in the sixteenth year and third month of his reign.”

Therefore, the Romans built Offa’s Dyke 700 years before Offa!

However, archaeologists are now finding Neolithic flints inside the ditch of the dyke – so how did they get there?

Romans are famous for ‘adapting’ – taking existing features, such as ditches and adding a defensive bank for their own use, as did the Normans who followed them a thousand years later in history. So Offa’s Dyke has nothing to do with Offa, but is this archaeological reality or misinterpretation key to why our history is not as it’s perceived? However, is there any evidence that this association with water contributed to these strange earthworks in prehistory?

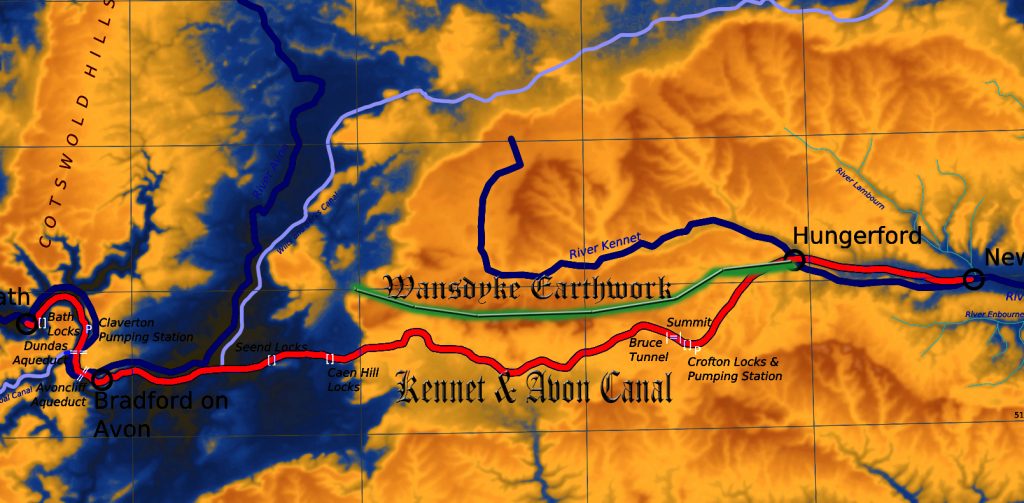

Wansdyke

According to Wikipedia, “Wansdyke consists of two sections of 14 and 19 kilometres (9 and 12 mi) long with some gaps in between. East Wansdyke is an impressive linear earthwork, consisting of a ditch and bank running approximately east-west, between Savernake Forest and Morgan’s Hill. West Wansdyke is also a linear earthwork, running from Monkton Combe south of Bath to Maes Knoll south of Bristol but less impressive than its eastern counterpart. The middle section, 22 kilometres (14 mi) long, is sometimes referred to as ‘Mid Wansdyke’ but is formed by the remains of the London to Bath Roman road. It used to be thought that these sections were all part of one continuous undertaking, especially during the Middle Ages when the pagan name Wansdyke was applied to all three parts.

East Wansdyke in Wiltshire, on the south of the Marlborough Downs, has been less disturbed by later agriculture and building and remains more clearly traceable on the ground than the western part. Here the bank is up to 4 m (13 ft) high with a ditch up to 2.5 m (8.2 ft) deep. Wansdyke’s origins are unclear, but archaeological data shows that the eastern part was probably built during the 5th or 6th century. That is after the withdrawal of the Romans and before the takeover by Anglo-Saxons. The ditch is on the north side, so presumably it was used by the British as a defence against West Saxons encroaching from the upper Thames Valley westward into what is now the West Country.

West Wansdyke, although the antiquarians like John Collinson considered West Wansdyke to stretch from south East of Bath to the west of Maes Knoll, a review in 1960 considered that there was no evidence of its existence to the west of Maes Knoll. Keith Gardner refuted this with newly discovered documentary evidence. In 2007 a series of sections were dug across the earthwork which showed that it had existed where there are no longer visible surface remains.

It was shown that the earthwork had a consistent design, with stone or timber revetment. There was little dating evidence, but it was consistent with either a late Roman or post-Roman date. A paper in “The Last of the Britons” conference in 2007 suggests that the West Wansdyke continues from Maes Knoll to the hill forts above the Avon Gorge and controls the crossings of the river at Saltford and Bristol as well as at Bath.

As there is little archaeological evidence to date the western Wansdyke, it may have marked a division between British Celtic kingdoms or have been a boundary with the Saxons. The evidence for its western extension is earthworks along the north side of Dundry Hill, its mention in a charter and a road name.

The area of the western Wansdyke became the border between the Romano-British Celts and the West Saxons following the Battle of Deorham in 577 AD. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the ‘Saxon’ Cenwalh achieved a breakthrough against the British Celtic tribes, with victories at Bradford on Avon (in the Avon Gap in the Wansdyke) in 652 AD, and further south at the Battle of Peonnum (at Penselwood) in 658 AD, followed by an advance west through the Polden Hills to the River Parrett. It is, however, significant to note that the names of the early Wessex kings appear to have a Brythonic (British) rather than Germanic (Saxon) etymology”.

Later scholars have often questioned the accuracy of the descriptions given by these antiquaries such as assertions that Wansdyke reached the Bristol Channel (Fox and Fox 1958) and even Asser’s statement that Offa’s Dyke ran from sea to sea (Hill and Worthington 2003 106). While some antiquarians were probably exaggerating the size of earthworks, we must be cautious of dismissing descriptions of the dykes from before they suffered the ravages of the Agricultural Revolution.

Some scholars went beyond merely describing the dykes and tried, often erroneously (with hindsight), to link them with known historical events like the Belgic invasions mentioned by Caesar or Caesar’s own invasion (Warne 1872 4-10; Guest 1883; Handford 1951 119-40). Among these early, rather speculative descriptions, the work of the Wiltshire historian Sir Richard Colt Hoare (1758-1838) stands out, not only in terms of the quality of his survey work but also his ability to differentiate between features of different dates, for example by realising that the central section of Wansdyke was actually a Roman road (Hoare 1812; Hoare 1821).1

For more information about British Prehistory and other articles/books, go to our BLOG WEBSITE for daily updates or our VIDEO CHANNEL for interactive media and documentaries. The TRILOGY of books that ‘changed history’ can be found with chapter extracts at DAWN OF THE LOST CIVILISATION, THE STONEHENGE ENIGMA and THE POST-GLACIAL FLOODING HYPOTHESIS. Other associated books are also available such as 13 THINGS THAT DON’T MAKE SENSE IN HISTORY and other ‘short’ budget priced books can be found on our AUTHOR SITE. For active discussion on the findings of the TRILOGY and recent LiDAR investigations that is published on our WEBSITE you can join our FACEBOOK GROUP.