Roman Ports miles away from the coastline – when sea levels are apparently rising.

“The difference between science and the fuzzy subjects is that science requires reasoning while those other subjects merely require scholarship.” – Robert A. Heinlein

When we look at old maps of Roman settlements or ports around Britain and the Mediterranean (we will look at these other roman ports outside Britain in part two of this blog), we see that most are built on the coastline or major waterways of these countries. This fact is not surprising as these locations would need a constant supply of commodities and goods for trading and construction.

Many historians believe that these towns were solely supplied by road – but the economics of this idea is flawed as road building, even with slaves (for someone has to feed and clothe them), is expensive, and the Roman army had absolute priority over the road system and its use. Most settlements and fortifications were built by the water, and if security was an issue, by a road as well, the other could be used as a backup in time of conflict.

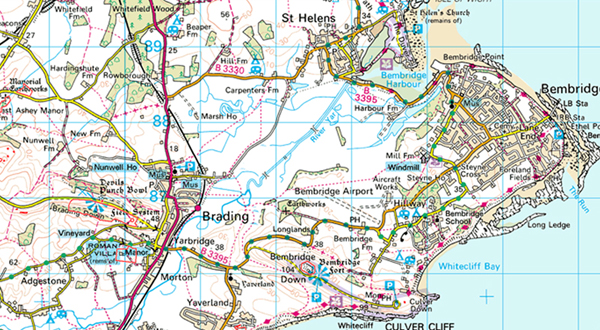

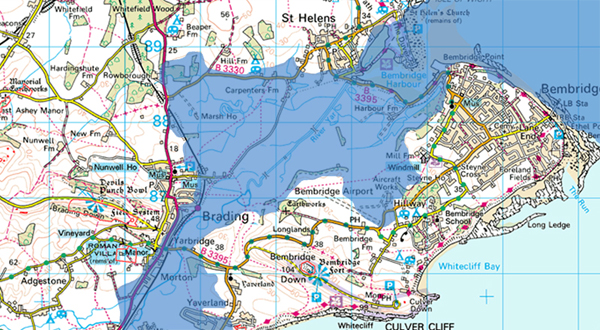

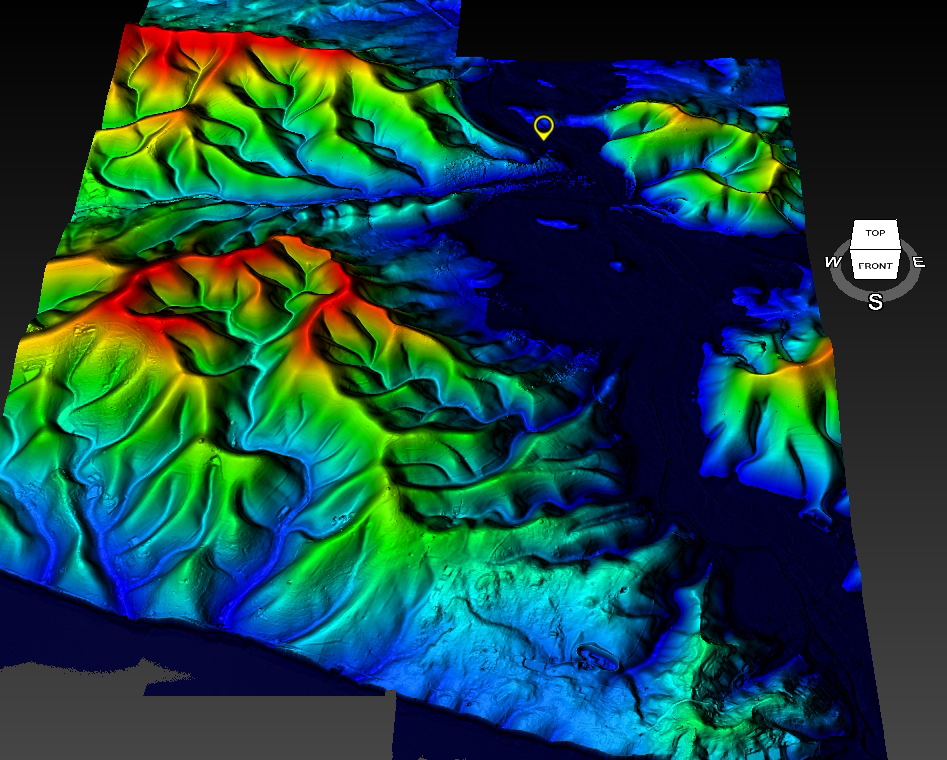

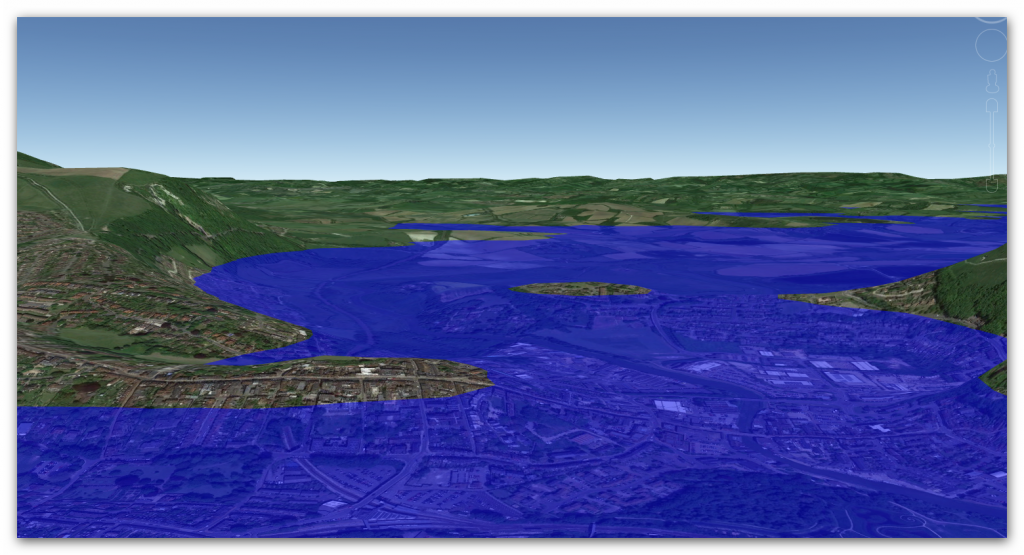

However, if we look more closely at these sites, it becomes apparent that some of the locations are far away from the shoreline or rivers that once supplied them. For example, the Roman town of Brading in the Isle of Wight is 3km from the sea and 500m from the nearest river, which is so small that it could hardly take a canoe, let alone a heavy ladened Roman ship.

At a date (which is impossible to specify), the East Yar valley of Brading became a tidal haven – it would seem to have been the same at the time of the Roman occupation in the first four centuries A.D. As such, Brading sat on the head of a sea inlet: the sea nourished its growth, allowing maritime trading activities which, by 1180, had earned it recognition as a ‘town’. East Yar is a natural Harbour surrounded by high hills allowing ships to shelter safely against inclement weather and high winds.

From around 6,000 BCE to A.D. 43, evidence of settlement in Brading by Mesolithic, Neolithic, Bronze and Iron Age peoples take the form of burial mounds of tribal chieftains at Nunwell Down, and weapons, tools, coins and jewellery from different sites. In 55-54 BCE, Julius Caesar invaded (briefly) Southern Britain; there is subsequent evidence of imported Roman wine and pottery from the Brading Roman Villa site. Claudius then invaded Britain again in A.D. 43, for a period lasting over 400 years.

An unchallenged governorship of the Island by Vespasian followed with Brading as its main port. The Villa in Brading probably had its origins before A.D. 100 and developed over the next 250 years, with mosaic floors laid around A.D. 320-340 in its most prosperous period. Alas, Pirate raids in about A.D. 367 marked the end of the Villa and the town’s systematic ransacking.

Consequently, we know that the harbour was in use for nearly 7000 years prior to it silting over.

When the ‘silting’ started (silting is the landing drying out to become land) and the harbour became less effective, other ports such as Newport (hence the name!) with a similar sheltered harbour, as well as Cowes started to be used. The final demise of Brading began in 1562, when a tendency towards the natural situation of the waterway combined with the enticing prospect of reclaiming more lucrative agricultural land prompted George Oglander and German Richards of Yaverland Manor to wall in the Oglanders’ North Marsh and other lands to the west of Bexley Point and up to Carpenters on the road to St. Helens.

Edward Richards built an embankment across the marshes to Centurion’s copse on the Bembridge side in 1594 and relocated the town quay to the end of Quay Lane on the seaward side of this embankment, which is now known as the Old Sea Wall. There were numerous pleas (documented from 1576 onwards) for merchants to be allowed access for their boats through these walls to the previous town quays, particularly that at Wade Mill, because their livelihoods were threatened.

The history books will tell you that this reclaiming of land was created by artificial drainage, but why would you wish to allow a thriving harbour to silt up if it was commercially viable?

If we look at a map of Brading, we see that the old harbour was fed by several rivers, which survive today in a shallower form; this indicates that this was a freshwater harbour and was connected to the sea. Another British harbour down the Shoreline in East Sussex is called Lewes and shows just how strange these ancient disappearing ports are and the reason for this mystery.

According to the history books:

‘The Ouse is one of the four rivers that cut through the South Downs. It is presumed that its valley was cut during a glacial period; since it forms the remnant of a much larger river system that once flowed onto the floor of what is now the English Channel. The extent of the inundation it experienced after the last ice age can be observed in the lower valley which would have flooded; there are ‘raised beaches’ 40 metres (Goodwood – Slindon) and eight metres (Brighton – Norton) above present sea level. The offshore topography indicates that the current coastline was also the coastline before the final deglaciation, and therefore, the mouth of the Ouse has long been at its latitude.’

Archaeological evidence points to prehistoric dwellers in this area. Scholars think that the Roman settlement of Mutuanton is was here, as quantities of artefacts have been discovered within the area. The Saxons also built a castle here, having first constructed its mote as a defensive point over the river; they gave the town its name.

However, the most interesting aspect of Lewes is that it is seven miles from the current Shoreline at Newhaven, and until recent history (last 2000 years), it was the main port of the South coast as it had a substantial natural shelter inland of the stormy seas. Moreover, there are stories that Lewes was the original landing point for Julius Caesar’s first invasion as it was the most extensive and safest harbour in Southern Britain’s mainland.

Today the River Ouse is just a sleepy river running through the café bar area of Lewes, yet in the recent past, the town would have been a fishing port with boats moored up next to what we see the retail High Street today. According to geologists, the sea levels have been rising since the great flood, after the last ice age and that the ‘Isostatic uplift’ from the same event is now in reverse and lowering the landscape to compound the sea level rises – so why has Lewes gone from an essential seaport to a small idyllic river with café bars?

In the Doomsday book (1086), the Ouse valley was still a tidal inlet with a string of settlements located at its margins. However, in later centuries, the Ouse was draining the valley sufficiently well for some of the marshland to be reclaimed as highly prized meadowland. The Ouse’s outlet at Seaford provided a natural harbour behind the shingle bar at this point in history.

However, by the 14th century, the Ouse valley was still regularly flooding in winter, and frequently, the waters remained on the lower meadows through the summer. In 1422, a Commission of Sewers was appointed to restore the banks and drainage between Fletching and the coast, indicating that the Ouse was affected by the same storm that devastated The Netherlands in the St Elizabeth’s flood of 1421. Drainage became so bad that 400 acres (1.6 km2) of the Archbishop of Canterbury’s meadow at Southerham were converted into a permanent fishery (the Brodewater) in the mid-15th century, and by the 1530s, the entire Lewes and Laughton Levels, 6,000 acres (24 km2), were reduced to marshland again.

Prior Crowham of Lewes Priory sailed to Flanders and returned with two drainage experts. In 1537 a water rate was levied on all lands on the Levels to fund the cutting of a channel through the shingle bar across the mouth of the Ouse (below Castle Hill at Meeching) to allow the river to drain the Levels.

This canalisation created access to a sheltered harbour, Newhaven (hence the name for a New Haven for boats), which succeeded Seaford as the port near the mouth of the Ouse. The new channel drained the Levels, and much of the valley floor was reclaimed for pasture. However, shingle continued to accumulate, and so the mouth of the Ouse began to migrate eastwards again. In 1648, the Ouse was reported to be unfit either to drain the levels or for navigation. By the 18th century, the valley was regularly inundated in winter and often flooded in summer.

What we can see here is with rising sea levels (and isostatic lowering of the land), the natural ground under this part of the South Downs is slowly drying out rather than getting wetter, which you would not expect as the sea level increased.

For more information about British Prehistory and other articles/books, go to our BLOG WEBSITE for daily updates or our VIDEO CHANNEL for interactive media and documentaries. The TRILOGY of books that ‘changed history’ can be found with chapter extracts at DAWN OF THE LOST CIVILISATION, THE STONEHENGE ENIGMA and THE POST-GLACIAL FLOODING HYPOTHESIS. Other associated books are also available such as 13 THINGS THAT DON’T MAKE SENSE IN HISTORY and other ‘short’ budget priced books can be found on our AUTHOR SITE. For active discussion on the findings of the TRILOGY and recent LiDAR investigations that is published on our WEBSITE you can join our FACEBOOK GROUP.